I wrote this note to my Old Testament Foundations students just now, and when I thought about it, I wondered whether it might help anyone else. I’ve removed any personal & relational details and hope they don’t mind.

It’s primarily about how Christians deal with fear, and it is not long. Some of you will still be feeling, as Luke Skywalker once said (yes, I’m one of those annoying Star Wars-quoting people), “I’m not afraid.” And I’m saying now, like Yoda, “You will be.”

That’s where I’d like to comment.

It’s getting beyond a joke now, isn’t it? We have all seen the charts. Infections are rising exponentially in most countries of the world. It’s the big one in our lifetimes. This is a time for Christians to show what the control of the Spirit of God does in a person’s life under pressure. Our Principal reminded us yesterday that Luther had some real wisdom to offer for plague situations. It reminded me that some of our Christian heroes lived with epidemics and had to man and woman up and face it like real believers.

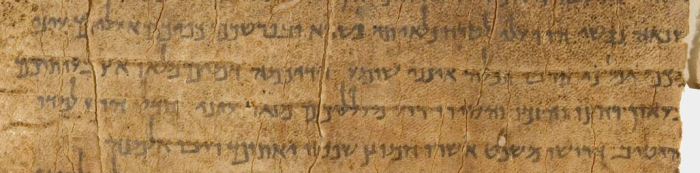

Let me share a scripture and then couch it in context. It’s Psalm 46:1-3:

God is our strong refuge;

he is truly our helper in times of trouble.

2 For this reason we do not fear when the earth shakes,

and the mountains tumble into the depths of the sea,

3 when its waves crash and foam,

and the mountains shake before the surging sea.

Read the whole psalm. It tells one side of the coin. We are not immune to fear either. I guarantee you that this situation is going to put chills down your spine in the coming days. Imagine the people of Judah’s feeling when “The snorting of the enemy’s horses is heard from Dan [in the far north] …They have come to devour the land and everything in it, the city and all who live there (Jer. 8:16).” What does Jeremiah say? Two verses later – “My heart faints inside me” (v. 18) and “Since my people are crushed, I am crushed” (v. 21). So we will face fear and sadness, especially for those around us – just not like those who have no hope (1 Thess. 4:13).

For ourselves, I believe the goal is to hold our life palm upward and fingers open. God can take it when he wishes. Then we can live freely. It’s those who are ready to die who are most ready to live. But these things come along to remind us how that’s done, and if it isn’t society-wide, it’s personal, a health scare or near-miss car accident.

It’s His breath, and its ours on loan.

So keep breathing.